Hi everyone,

After posting last week’s roundup of structure tips for memoirists, I recalled a class I once taught on structuring the personal essay. I’d been inspired by two fabulous craft essays, one by master essayist John McPhee and the other by memoirist Tim Bascom. I thought I’d better share those sources with you, too.

And to set them up, a few words about the personal essay as a form unto itself, related but distinct from memoir, and why it should interest you!

What is a Personal Essay?

The personal essay is arguably the most marketable and variable of literary forms. Op-eds, New Yorker and Vanity Fair and Harper’s articles, newspaper columns, flash nonfiction, and travel pieces all qualify as personal essays. So do many books of nonfiction. And some Substack blogs. Bottom line: writers of all genres need to master this form, if only for the purpose of promoting other projects, like books or films or classes.

Form follows function. Whether you choose a straight shot through time or a complicated minuet, the structure you end up with should clarify the reader’s journey in a way that illuminates the essay’s underlying significance.

Here are a few ways the personal essay compares with memoir and other genres:

The personal essay can be about almost anything, while the memoir tends to examine private memories, especially striking or life-changing experiences.

Like memoir, every personal essay is rooted in a central question. In both forms, the process of investigation is at least as important as the final answer or resolution of that question.

But the personal essay doesn’t necessarily seek to make sense out of life experiences; rather, these essays tend to let go of that sense-making impulse to do something else, like nose around a bit in the wondering, uncertain space that lies between experience and the need to explain or organize it in a logical manner.

Because the personal essay explores, free from any need to interpret, it’s generally lighter than the memoir, which mines the past to shed light on the present, excavating a life. The goal of the personal essay is to express subjective inquiry in a way that persuades the reader of the significance of the investigation; it’s not always meant to peel back the layers of self.

The essay is more open than poetry and fiction in that it allows for more of the world and its languages, its arts and food, its sport and business, its travel and politics, its sciences and entertainment, to be present, valid and important, coming to the surface instead of coded into metaphor or subtext.

Like a memorist, an essayist always writes two essays simultaneously, overlapped as transparencies, one exploring what Vivian Gornick calls the situation, the other what she terms the story. Poet Richard Hugo talks about a piece’s “triggering subject” and its generated, or real, subject. Phillip Lopate describes the “double perspective” that an essayist needs, the ability to both dramatize and to reflect. I’ve always talked to my writing students about the narrow subject and the larger subject.

An essay that deliberates on its narrow subject exclusively can be a pleasing essay, lingering affectionately on sensory description, on evocation of time and place, on regional history, maybe on relevant stories. But that essay’s larger subject is what will draw readers forward, asking not just What happened, but Why it’s significant. Even the narrowest essay must ultimately turn and deliver a Why that’s resonant and memorable.

Structure tips from two masters

Remember that all written structure is comprised of patterns. The narrative may move backward and forward in time at intervals. Expository backgrounders may alternate in sequences with vignettes or dramatic scenes. First person book-enders may frame a more journalistic investigation. But the selection of patterns is not arbitrary. Form follows function. Whether you choose a straight shot through time or a complicated minuet, the structure you end up with should guide the reader’s journey in a way that illuminates the essay’s underlying significance.

It helps — immensely— to visualize your structure. Once you can picture the sprigs of pattern within your work, you can start to see how the whole essay naturally will lay out. This process applies to writing of all types, of course, but personal essays may lend themselves to more complex designs. As Tim Bascom explains, “the best essayists resist predictable approaches. They refuse to limit themselves to generic forms, which, like mannequins, can be tricked out in personal clothing. Nevertheless, recognizing a few basic underlying structures may help an essay writer invent a more personal, more unique form.”

These two invaluable craft essays will help you find the structure that best supports your story.

Structure

By John McPhee—New Yorker, January 6, 2013

newyorker.com/magazine/2013/01/14/structure

I’m sorry that this article is behind a paywall, but if you subscribe to the New Yorker, it’s well worth your time to fetch it from the online archives and settle into it. Although it’s long, it will give you an immersive sense of McPhee’s process as he wrestled, often agonizingly, with the structures for some of his most memorable essays.

Here are a few of his many take-aways:

The approach to structure in factual writing is like returning from a grocery store with materials you intend to cook for dinner. You set them out on the kitchen counter, and what’s there is what you deal with, and all you deal with… To some extent, the structure of a composition dictates itself, and to some extent it does not. Where you have a free hand, you can make interesting choices.

An essential part of my office furniture in those years was a standard sheet of plywood—thirty-two square feet—on two sawhorses. I strewed the cards face up on the plywood. The anchored segments would be easy to arrange, but the free-floating ones would make the piece. I didn’t stare at those cards for two weeks, but I kept an eye on them all afternoon. Finally, I found myself looking back and forth between two cards. One said “Alpinist.” The other said “Upset Rapid.” “Alpinist” could go anywhere. “Upset Rapid” had to be where it belonged in the journey on the river. I put the two cards side by side, “Upset Rapid” to the left. Gradually, the thirty-four other cards assembled around them until what had been strewn all over the plywood was now in neat rows. Nothing in that arrangement changed across the many months of writing.

Almost always there is considerable tension between chronology and theme, and chronology traditionally wins. The narrative wants to move from point to point through time, while topics that have arisen now and again across someone’s life cry out to be collected. They want to draw themselves together in a single body, in the way that salt does underground. But chronology usually dominates… After ten years of it at Time and The New Yorker, I felt both rutted and frustrated by always knuckling under to the sweep of chronology, and I longed for a thematically dominated structure.

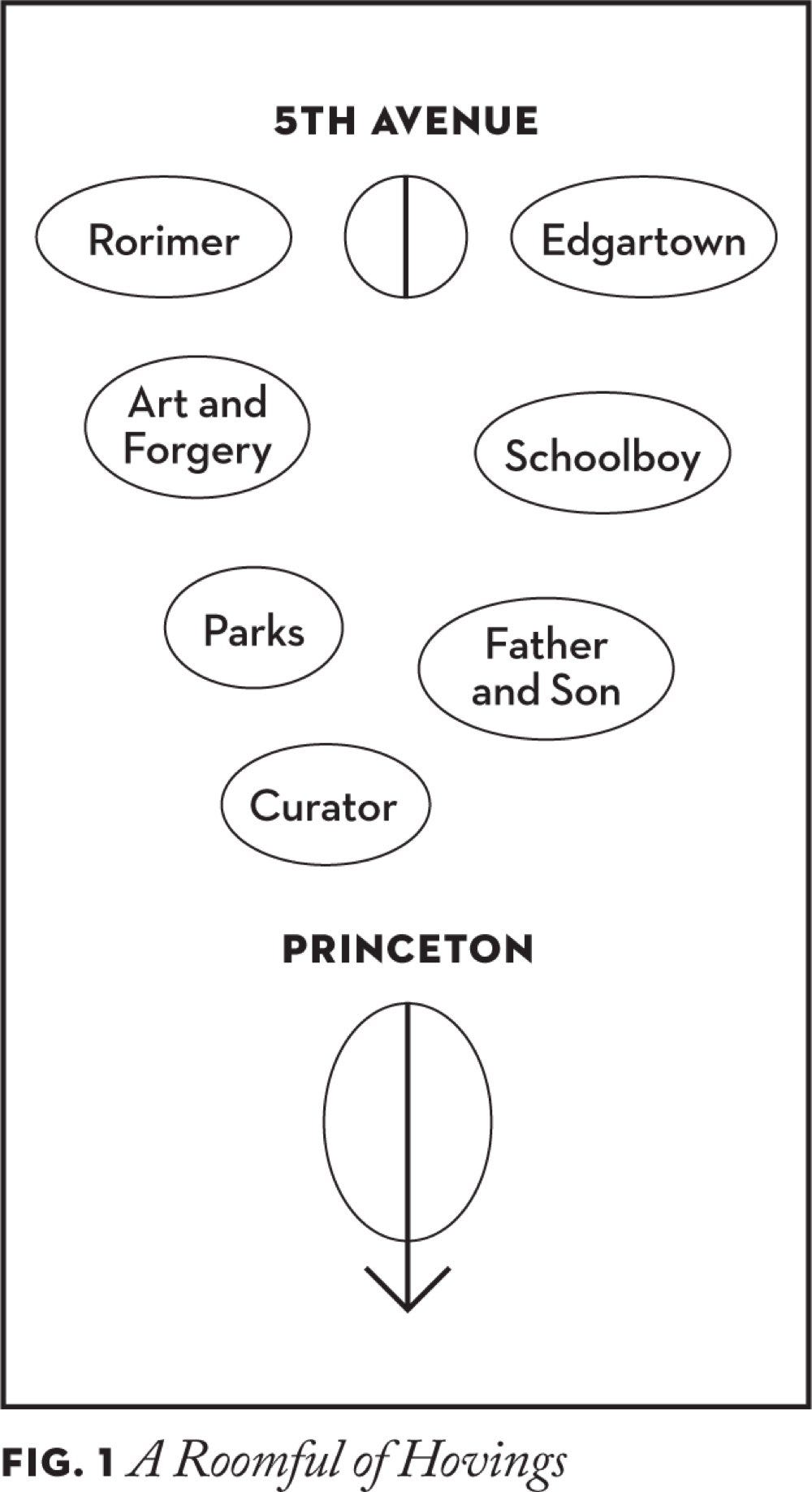

I remembered a Sunday morning when the museum was “dark” and I had walked with Hoving through its twilighted spaces, and we had lingered in a small room that contained perhaps two dozen portraits. A piece of writing about a single person could be presented as any number of discrete portraits, each distinct from the others and thematic in character, leaving the chronology of the subject’s life to look after itself (Fig. 1).

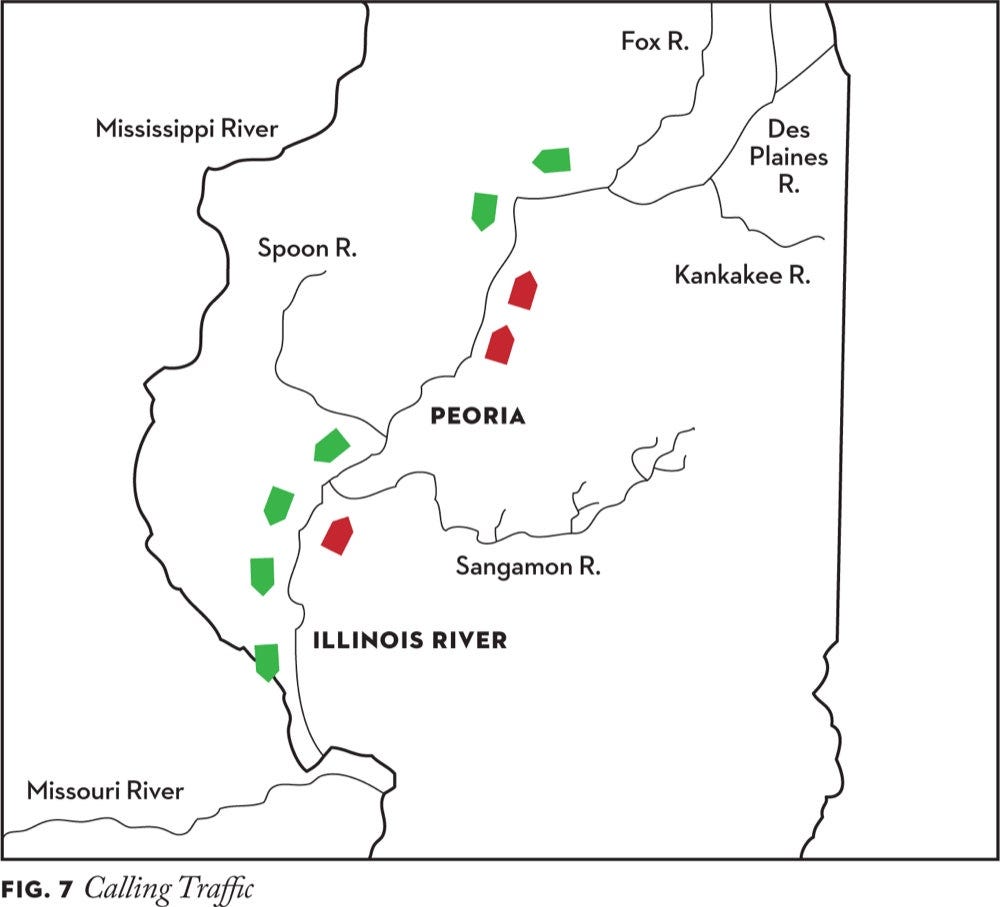

There was no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end. If ever there was a journey piece in which a chronological structure was pointless, this was it. In fact, a chronological structure would be misleading. Things happened, that’s all—anywhere and everywhere. And they happened in themes, each of which could have its own title at the head of a section, chronology ignored…The over-all title was “Tight-Assed River.” There were eight sections. One section’s title was “Calling Traffic” (Fig. 7). The arrows coincide with places where things happened, such as Creve Coeur Landing, Kickapoo Bend. But they are not consecutive in the story. Their colors correspond to the colors of channel buoys—red closer to the left bank, green closer to the right bank.

If you have come to your planned ending and it doesn’t seem to be working, run your eye up the page and the page before that. You may see that your best ending is somewhere in there, that you were finished before you thought you were.

Picturing the Personal Essay: A Visual Guide

by Tim Bascom—CNF Quarterly, Summer 2013

creativenonfiction.org/writing/picturing-the-personal-essay-a-visual-guide/

If you’ve read this far, you’re in luck! Bascom’s essential essay is FREE online. Please devour!

This article will guide you through some of the forms I mentioned last week — the circular, braided, and chronological structures. But Bascom also unpacks more complex spiral, chain, and layered approaches that echo McPhee’s. He illustrates each structure both with graphics and examples from well-known writers, including Jo Ann Beard, Virginia Woolf, Annie Dillard, and Judith Ortiz Cofer.

Here are some nuggets:

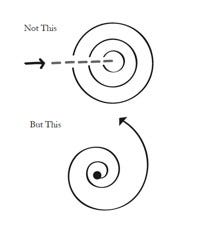

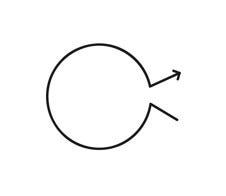

Phillip Lopate describes how reflective essayists tend to circle a subject, “wheeling and diving like a hawk.” Unlike academic scholars, they don’t begin with a thesis and aim, arrow-like, at a pre-determined bull’s-eye. Instead, they meander around their subject until arriving, often to the side of what was expected:

An example of the spiral essay is “Meander” by Mary Paumier Jones: LINK

Think of the essayist looking through a viewfinder to limit the reader’s focus.

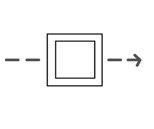

The act of framing a selected portion of raw experience from the chronological mess we call “life” fundamentally limits the reader’s attention to a manageable time and place, excluding all events that are not integrally related. What appears in the written “picture,” like any good painting, has wholeness because the essayist was disciplined enough to remove everything else.

An example of the segmented, or chain, essay is this “Address” by A. Papatya Bucak: LINK

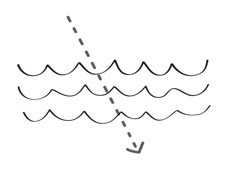

Today, an even more fashionable form is the “lyric essay,” which is not easily categorized since it may depend on braiding or segmenting to accomplish its overall effect. However, like the lyric poem, the lyric essay is devoted more to image than idea, more to mood than concept. It is there to be experienced, not simply thought about. And like many poems, it accomplishes this effect by layering images without regard to narrative order. A lyric essay is a series of waves on the shore, cresting one after the other. It is one impression after another, unified by tone. And it seems to move in its own peculiar direction, neither vertical nor horizontal. More slant:

An example of the lyric essay is “Gyre” by Diane Seuss: LINK

In real life, there is always an “and then,” even if it comes after we have died. So the best conclusions open up a bit at the end, suggesting the presence of the future… something yet to be realized. The ending both closes and opens at the same time.

An example of the circular essay is “Hazmat” by David Jauss: LINK

Thanks so much for being here! I’d love to get to know you and your writing. Become a paid subscriber to join my chat and participate in our Write On! Roundups, where I draw on 40 years of publishing and MFA experience to answer your questions. Or, feel free to leave questions in the comments below!

P.S. This is a post from MFA Lore, my craft section for creative writers. If you’re feeling overwhelmed by emails and only want to receive posts about Chinese-AmericanLegacy, please don’t unsubscribe! You can change your settings to receive only one section. Learn how to manage your subscriptions HERE.